Captain Steve Kerchner

A Day in the Life of a Shrimper

story and photos by TIM BARNWELL

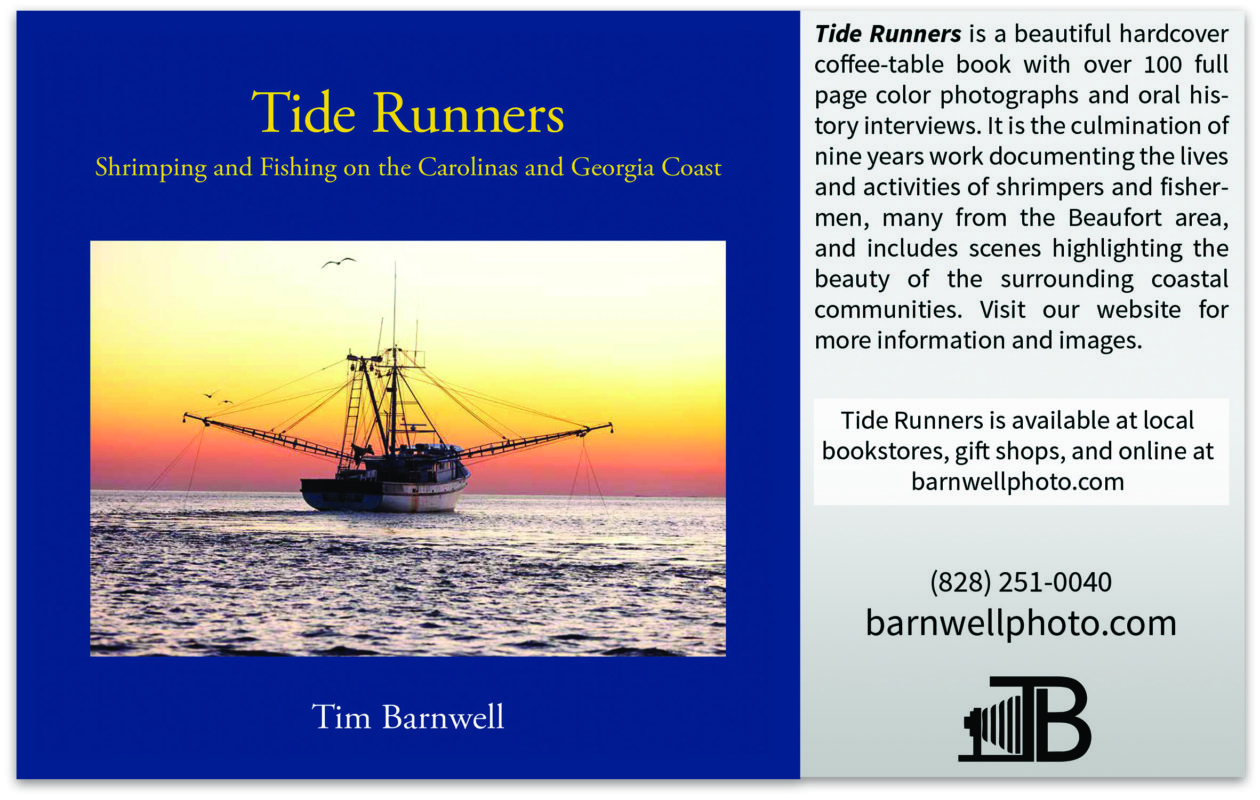

Beaufort County has a long history of shrimping, and while many are curious about what goes on out there on the ocean, few have had the opportunity to board a shrimp trawler. When I first started my Tide Runners: Shrimping and Fishing on the Carolinas and Georgia Coast book project, I had a romantic idea of what it must be like to be on one of the many boats I saw on the horizon. However, after numerous trips with different captains, I realized how different it was than I had imagined and gained a more realistic understanding of the hard work and long hours required to make a living as a shrimper.

Beaufort County has a long history of shrimping, and while many are curious about what goes on out there on the ocean, few have had the opportunity to board a shrimp trawler. When I first started my Tide Runners: Shrimping and Fishing on the Carolinas and Georgia Coast book project, I had a romantic idea of what it must be like to be on one of the many boats I saw on the horizon. However, after numerous trips with different captains, I realized how different it was than I had imagined and gained a more realistic understanding of the hard work and long hours required to make a living as a shrimper.

One of the captains I ventured out with was Steve Kerchner, who shrimped the waters around Beaufort for forty years before retiring recently. His boat, the Poor Boy, was a 65-foot trawler last based at the St. Helena seafood dock on St. Helena Island. A typical day during the season started with him rising early, having a quick breakfast, then leaving the house around 3 a.m. On the way to the dock, he would stop to pick up his two helpers. Together, they would prep the boat, take on fuel and ice, and try to leave the dock by 4 a.m. As the Poor Boy had a shallower draft than typical shrimp boats, it could leave the dock and head up the creek before others who needed to leave on the high tide. From the dock, it would typically take him 45 minutes to an hour and a half to reach the spot where they were to drop their nets, usually by 5-5:30 a.m.

One fall morning, I was invited along to document Captain Kerchner and his crew’s activities. I arrived at the dock at 4:30 a.m. and joined them for the day. Once on-site at their first spot, the outriggers were lowered, and the nets dropped into the water—cables, ropes, and winches flying. Over the next few hours, Steve would pilot his craft through the waters off the coast as the nets dragged along the bottom of the ocean. A “try” net was lowered occasionally to gauge whether they were catching shrimp. Every two to three hours, as the nets filled, he could feel the drag increasing and boat slowing; the nets were hauled in and emptied on deck into a sorting box. The nets were then returned to the sea for another drag while the strikers stood around the box and picked out and threw back the bycatch before sorting the shrimp, roughly by size, into laundry-style baskets. The shrimp were then iced down and stowed until the boat returned to dock for unloading.

The process was repeated as time permitted and if they were catching shrimp in sufficient numbers. Most days, he would do multiple drags; if they were catching shrimp, he would stay. In the summer months that could mean until seven or eight o’clock in the evening. That is not necessarily going to happen every day. The controlling factor is whether you are making money. Steve says the frustrating thing about it is that you do not set the schedule. The shrimp and the weather determine how long he works. Also, the moon phase is a significant factor as the shrimp move back and forth between the ocean and the estuaries on the big tides, which is on the full moon and the new moon. The estuary areas are closed to all fishing, so you can only catch shrimp when they are in open waters.

Steve said he needed to net a minimum of $1,000 worth of shrimp a day, at a bare minimum, to stay in operation. That is to pay for fuel, ice, crew, repairs, and nets, and the general cost of doing business. Size, weight, quantity, and market price are the key factors in determining the price he would receive from the dock owner. Some days he would catch many small shrimp, but they would not be worth much, while other days he’d catch fewer, larger ones that would be worth more money. The U.S. shrimp fleet catches less than 10 percent of what is consumed in our country, so captains have little control over the price they get for their shrimp, even while their operating costs continue to climb.

The shrimpers typically sell all their catch to the dock where they operate. The dock owner acts as a broker. The dockworkers weigh the shrimp and pack them into 50- or 100-pound boxes. At the end of the week, the captain would get a ticket saying how much shrimp they unloaded, at what size and price, then deduct how many gallons of fuel and ice were purchased, and they would get a check for the balance. Typically, captains would unload every second or third day as it takes so much time at the dock, so the shrimp would be kept on ice. On the Poor Boy, Steve would go through 6,000-10,000 pounds of ice a week.

At the end of the day, back at the dock, the catch would be unloaded, the boat and gear would be cleaned and stowed, and repairs made to anything broken. Usually, that’s net mending, rigging, or winch repairs. Once the boat has been hosed down and gear stowed, the crew heads home to get a few hours of rest before they start another day. During the season, which might run from the first of May to the end of December, Steve would typically work 140-150 days. That is just shrimping, not counting days working on the boat, attending to breakdowns, etc.

So the next time you sit down for a meal at a seafood restaurant that features local shrimp, think about all the long hours and hard work that went into catching the shrimp arrayed on your plate, and you can better appreciate the effort that goes into your great wild-caught meal.

Tim Barnwell is a photographer based in Asheville, NC, and author of seven books including Tide Runners: Shrimping and Fishing on the Carolinas and Georgia Coast.