Victoria Smalls

Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, Protecting the Culture and the People

story by NAKEISHA DAWSON-THOMPSON

photos by PAUL NURNBERG and courtesy of GULLAH GEECHEE CORRIDOR

Victoria Smalls, of St. Helena Island, serves as the executive director of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor. The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor is the National Heritage Area program and is managed by the U.S. National Park Service. Congress designates National Heritage Areas (NHAs) as places where natural, cultural, and historic resources combine to form a cohesive, nationally significant landscape. The purpose of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor NHA is to preserve, share, and interpret the history, traditional cultural practices, heritage sites, and natural resources associated with Gullah Geechee people of coastal North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Victoria Smalls, of St. Helena Island, serves as the executive director of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor. The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor is the National Heritage Area program and is managed by the U.S. National Park Service. Congress designates National Heritage Areas (NHAs) as places where natural, cultural, and historic resources combine to form a cohesive, nationally significant landscape. The purpose of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor NHA is to preserve, share, and interpret the history, traditional cultural practices, heritage sites, and natural resources associated with Gullah Geechee people of coastal North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

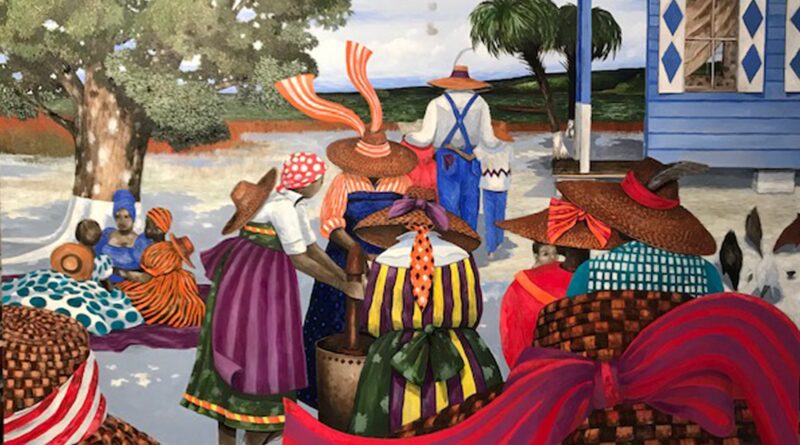

Gullah Geechee people have ancestors from Western and Central Africa — historically selected for their expertise in growing, planting, and cultivating rice on sites of enslavement here in the United States. Victoria remembers, as a youth, that she believed rice came from Asia, and she had no idea that rice came from African nations, like Senegal and Angola. Gullah Geechee people were experts at growing and cultivating rice, indigo, and cotton. Specifically in this region, Sea Island cotton grew well in this subtropical climate. The difference between regular cotton and Sea Island cotton is that Sea Island cotton can grow up to eight feet tall. The triangular slave trade was another form of bringing immense wealth to the enslavers and plantation owners.

The Gullah Geechee Corridor spans four states, 27 counties, and 12,000 square miles. To date, there are many different perspectives or meanings for the words “Gullah” and “Geechee.” For years, Geechee has been frowned upon and looked at as uneducated, bad-talking, broken English-speaking folks. The language of Gullah Geechee people had been forged during the Middle Passage and after the enslaved Africans arrived in the United States. The many different African languages, food, art forms, storytelling, oral history, spirituality, and supernatural beliefs of the power of the land and waters melded together. Tight-knit villages were forged by this melding of the people’s cultures. As enslaved people, learning English was essential to perform tasks and to survive on the plantations. After slavery ended, freedmen came together for survival and self-determination, and forged tight-knit communities where the Gullah Geechee culture was vital to them to preserve and pass down through generations. Many fled to seek better opportunities because of racial persecution, domestic terrorism, and fear for their lives. Large numbers of Gullah Geechee people fled and spread throughout the U.S. Through this great exodus, some people had to shed their culture because it was not fashionable in larger cities. However, some retained their culture in different ways, including the language.

Although Gullah Geechee people have ancestry from multiple African countries and tribes, many think Gullah comes from the “Gola” tribe or Angola, Kissi tribe pronounced (Keysee), or Geesee. Locally, the Ogeechee River became a border whether you called yourself Gullah or Geechee. Victoria explains that more than 5,000 West African words and names make up the Gullah language. Living here in the Lowcountry, you can still hear some of these words, names, or phrases currently. Day clean means dawn or morning. Binya means someone who is from this area. Cumyah means someone who has come from somewhere else to this area. Gullah is ever-evolving; each generation has taken traditional parts of the Gullah culture and blended them with new pieces of the culture.

on the Smith Plantation in Port Royal, SC

The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor has done fantastic work in the preservation of the historical Gullah Geechee culture in many ways. Congressman James Clyburn has been a great spokesperson for preserving the Gullah Geechee heritage. The heritage needs the federal government’s protection to ensure the Gullah Geechee culture and way of life aren’t lost due to irresponsible development and regentrification threats. The Gullah Geechee thrives because of community members’ self-determination, ancestral land preservation, and love for one another.

To this day, Gullah families have purchased and held onto their ancestral land for more than 150 years. Victoria’s family is one of those families who still own their land. Historically, St. Helena Island was predominantly Gullah Geechee for many years.

The traditional Gullah Geechee diet included locally grown produce such as vegetables, fruits, game, seafood, and livestock, as well as foods from Africa brought over by slave traders like okra, rice, yams, peas, hot peppers, peanuts, sesame “benne” seeds, sorghum, and watermelon. Native Americans also introduced foods like corn, squash, tomatoes, and berries. In the southern coastal districts, rice became the main crop for both Gullah Geechee natives and whites.

Enslaved people made the most of the food (or rations) at hand, stretching a little food a long distance, supplementing with fish and game, having leftovers from slaughtering, and sharing communal stews with neighbors. Enslaved people frequently used African cooking techniques and ingredients in plantation kitchens. Because enslaved women made up the majority of plantation cooks, a significant portion of the cuisine we now refer to as “Southern” was developed by and required the work of enslaved chefs.

Gullah Geechee is a unique creole language spoken in the coastal areas of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. The Gullah Geechee language began as a simplified form of communication among people who spoke many different languages, including European slave traders, enslavers, and diverse African ethnic groups. The vocabulary and grammatical roots come from African and European languages. It is the only distinctly African creole language in the United States and has influenced traditional Southern vocabulary and speech patterns.

As a young girl, Victoria recalls how she would watch the nightly news to learn to change her speech because people would laugh at her when she spoke in her first language (Gullah Geechee). She is not fluent in Gullah Geechee, but when she is around family members, Gullah Geechee comes out in conversation. Many elders can speak fluent Gullah Geechee, and many who have ventured into different workforces have learned to “code switch” or language assimilation. There is still a stigma that those who speak the Gullah Geechee language are uneducated and can’t speak proper English. It is important to Victoria and the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor to continue to encourage the descendants of those enslaved Africans, who built the Gullah Geechee culture here in the U.S., to learn the values and ways of life of the Gullah Geechee people and the significant contributions they’ve made to this country.

Moving forward, Victoria states she would love to see the Gullah Geechee language taught in schools and local, state, and federal government assistance to protect and preserve Gullah Geechee land (as many of the people are being taxed out of their land and imminent domain). The goal of the Gullah Geechee Corridor is to hold open forums each year on education, land preservation, sea-level rise, and climate change, where they converge to speak up on efforts being made to preserve, disseminate, and interpret the Gullah Geechee people’s history, traditional cultural practices, heritage sites, and natural resources. To share information from these meetings and about the work being done throughout the Corridor to advance these aims, they publish a newsletter and hold quarterly meetings at the Corridor.

Moving forward, Victoria states she would love to see the Gullah Geechee language taught in schools and local, state, and federal government assistance to protect and preserve Gullah Geechee land (as many of the people are being taxed out of their land and imminent domain). The goal of the Gullah Geechee Corridor is to hold open forums each year on education, land preservation, sea-level rise, and climate change, where they converge to speak up on efforts being made to preserve, disseminate, and interpret the Gullah Geechee people’s history, traditional cultural practices, heritage sites, and natural resources. To share information from these meetings and about the work being done throughout the Corridor to advance these aims, they publish a newsletter and hold quarterly meetings at the Corridor.

If you want to learn more about the Gullah Geechee National Heritage Area, visit their website at www.gullahgeecheecorridor.org.