Catherine Scarborough

Life of Service Includes an Unexpected Box of Chocolates

story by JEANNE REYNOLDS photos by SUSAN DELOACH

In a long career devoted to service and helping others, the one job Catherine Scarborough never imagined was the one she got when Paramount Pictures came to Beaufort to film Forrest Gump 30 years ago.

In a long career devoted to service and helping others, the one job Catherine Scarborough never imagined was the one she got when Paramount Pictures came to Beaufort to film Forrest Gump 30 years ago.

“It started with the location for Bubba’s mother’s house,” Catherine recalls of her venture into the lights, camera, and action world of a Hollywood production. “I was renovating a house I owned on Lucy Creek at the end of Sams Point Road, and one day, I noticed some big, expensive cars pulling off and people walking around. One of the drivers told me it was people from Paramount Pictures working on a movie, and they wanted to use my house for some of the scenes.”

The movie was going to be based on a quirky, little-known novel by Winston Groom: Forrest Gump.

“I said OK, but I’ve never heard of it, so I have to read the book first to see what it’s about and make sure it’s alright,” she says.

She did, and the deal was inked. But the story doesn’t end there. When Paramount began casting extras for the film, a group of Catherine’s girlfriends wanted to try out for parts and convinced her to drive them to Charleston to audition.

“They told me I should try out, too,” Catherine says. “I’m not an actress, but I filled out an application anyway and just put some funny, nonserious answers to the questions. I guess they liked that because they called me back for an interview in Beaufort.”

When she got to the interview, she quickly noticed every Hollywood hopeful in the room was a small, brown-haired woman. It turned out the role they were competing for was the stand-in and double for Sally Fields, who played Forrest Gump’s mother in the movie. Whether it was the sense of humor that came through in her application or because she was local and was already part of the production due to her river house, Catherine got the job.

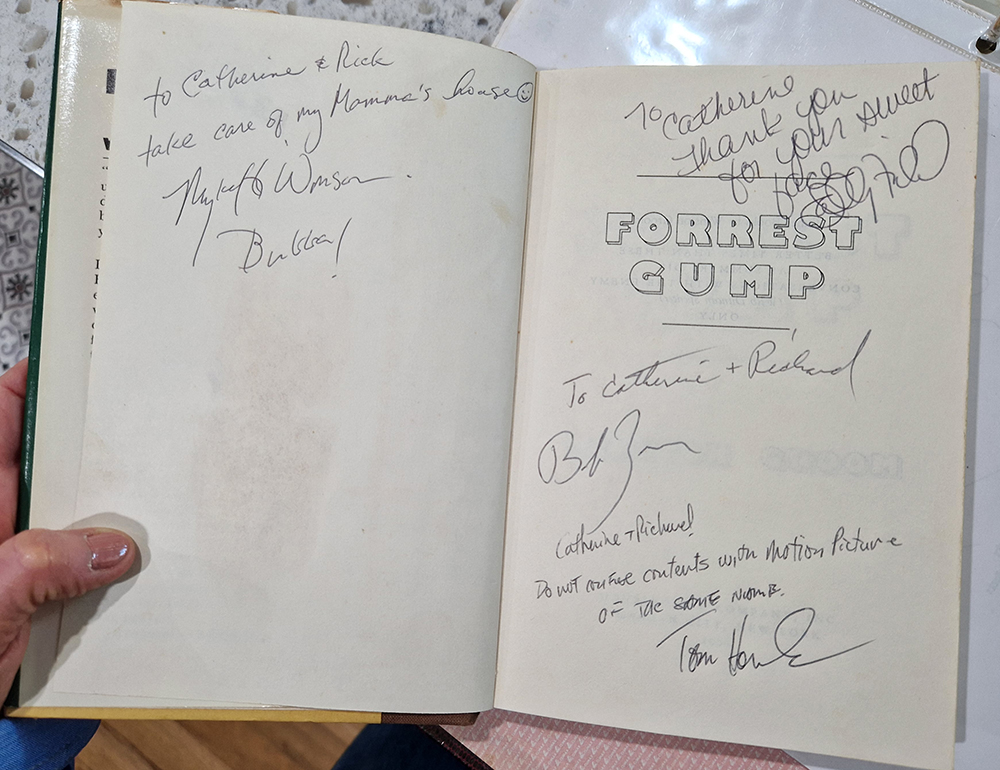

A movie stand-in isn’t exactly glamorous work, involving hours of standing around in the places the star will eventually perform while the crew checks lighting, sound, blocking, and other technical aspects of production. But she did get to meet actors Tom Hanks and Gary Sinise, got the entire cast to sign her copy of the book — oh, and apparently provided some helpful acting tips for Fields.

“One of the first days on the set, they were shooting the scene where Forrest’s mother is putting him on the bus, sending him off to school for the first time,” Catherine remembers. “I don’t have children, so I didn’t know what that would be like. But I thought of how I talk to my dogs, so I leaned down, grabbed his face, and said the line that way. The director told Sally Fields, ‘Watch how she does it and do it like that.’”

A HEALTHY BEGINNING

If Catherine had gotten a speaking role in the movie, she wouldn’t have had to fake a Southern accent as many actors try to do. She was born in the (then) small town of Moncks Corner in Berkeley County and graduated from Berkeley High School, where she was head cheerleader, ran track, and played basketball despite her diminutive size. “I was extremely fast and a good dribbler,” she says.

She earned a bachelor of science degree in health education from the University of South Carolina, and then returned home to teach environmental education, biology, and health in the county’s middle and high schools for a year. But teaching family life education was her passion, so when a position opened in Beaufort County as a school health coordinator, she eagerly moved to Beaufort.

“I just fell in love with it,” she says. “I decided to stay here.”

But within a few years, she met her first husband, Rick Ceips, and moved with him to Charleston so he could attend medical school. Catherine began working for the Washington, D.C.-based National Health Screening Council for Volunteer Organizations, a nonprofit group that pioneered the idea of community health fairs across the country.

But within a few years, she met her first husband, Rick Ceips, and moved with him to Charleston so he could attend medical school. Catherine began working for the Washington, D.C.-based National Health Screening Council for Volunteer Organizations, a nonprofit group that pioneered the idea of community health fairs across the country.

“It was a wonderful organization,” Catherine says. “We would set up week-long health screening events that 10,000–12,000 people would go through.”

Her husband’s medical education took the couple to Roanoke, Virginia, then back to Charleston. At each stop, Catherine continued to seek out and serve in the health field, as a health education consultant at Lewis-Gale Hospital in Roanoke, teaching others how to create health promotion programs, and then as community service and volunteer director at the Medical University of South Carolina — a job that included an unexpected opportunity to help save the hospital’s historic St. Luke’s Chapel when Hurricane Hugo devastated Charleston in 1989. After the storm, she discovered the large Tiffany stained-glass window had blown out of the back wall of the church onto the street, lying atop an iron grate and miraculously intact. Catherine organized its removal to a nearby doctor’s office for safekeeping, then geared up her volunteers on a T-shirt sales project to raise money to rebuild the church.

After a brief stint in Little Washington, North Carolina, in another hospital volunteer director role, Catherine and Rick returned to Beaufort. “I always wanted to come back to Beaufort,” she says, “and Beaufort needed an ophthalmologist, so we purchased an office here.”

DRAWN INTO PUBLIC SERVICE

Catherine worked in her husband’s practice at first. But the trajectory of her career shifted when she met U.S. Rep. Floyd Spence, whose district included Beaufort.

“He needed a part-time office person in Beaufort,” Catherine says. “It was community service work, helping people with their issues and accessing government. I loved constituency services, dealing with people and their needs.”

Five years as a field representative for a powerful 16-term Congressman and then his replacement, U.S. Rep. Joe Wilson, gave Catherine insight into politics at the state level as well — experience that served her well when a seat representing Beaufort in the S.C. House of Representatives came open.

“People asked me to run, but I wasn’t particularly interested,” Catherine says. “Then I thought, ‘Maybe I should look into it.’ So I decided to run and pretty much walked door to door all summer.”

Pounding the pavement paid off: She won that election and continued to serve in that office until 2007, when she was elected to fill an unexpired term in the S.C. Senate, becoming the only woman serving in that body and just the 10th woman ever to hold office in the S.C. Senate.

“I enjoyed working in the House,” Catherine says. “I wrote serious legislation.”

That included a human trafficking bill — the first passed in a state that mirrored the federal law — a federal fingerprint and DNA bill known as Katie’s Law that ensured information on convicted felons would go into a national database, $5 million in funding to preserve the beach at Hunting Island, and a project to widen Highway 17 to four lanes between Beaufort and Jacksonboro.

“It was deemed the most dangerous 22-mile stretch of highway in America,” Catherine says. “You could about set your watch by it — there would be an accident every day.”

“When you’re in office, you have real work to do for your constituents. You don’t just sit on the back seat,” she adds. “You gain lots of supporters and lots of enemies.”

One of those supporters was Wallace Scarborough, a colleague in the S.C. House, serving on the committee responsible for roads and bridges who helped secure funding for the Highway 17 project. Their professional relationship eventually became personal when Catherine’s husband died in 2006, Wallace divorced in 2007, and both lost re-election campaigns in 2008. They married in 2009 in the “Bluff House” — officially the Means-Gage House on the National Register of Historic Places — the circa 1790 home they own on Bay Street.

Her careers in politics and health education may be behind her, but Catherine continues to be drawn into serving the community, protecting the environment, and learning. Restoring their home led to a new interest in amateur archaeology when they discovered a trove of artifacts buried in an old privy in their backyard. They’re also pursuing protection for local bottlenose dolphins whose feeding grounds are endangered by plans to expand the City’s marina along Bay Street.

“I enjoy working on things, improving things, finding things,” Catherine says. “I think the common thread through my life has been helping people and public service. It was a great privilege and honor to serve the people of Beaufort County. Things happen for a reason. There’s a plan for your life, and you have to live within that. I look for the good, and I have faith that things are good.”