PRESERVING FORT FREMONT

story by KATE HAMILTON PARDEE photos courtesy of FRIENDS OF FORT FREMONT

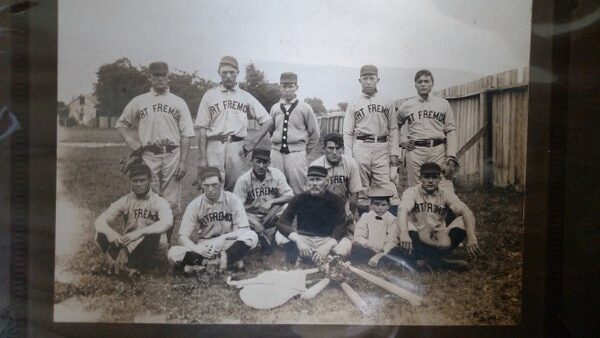

Behind every remarkable historic site is a story — not just of the place itself but of the role of Fort Fremont, which did not decrease after the Spanish-American War. Regular army troops did not arrive until March 1899 after the war. Before that, NC and SC volunteer troops were raised for the Spanish-American War and manned the fort. The fort had a conventional coast defense role under the army after the war. The decision to move the navy yard to Charleston in 1901 led to the fort being superfluous. The dry docks opened in Charleston in 1909. The troops at Fort Fremont were transferred to Texas in 1911, and only a detachment was left at the fort until it was disposed of.

People are dedicated to preserving it. Fort Fremont’s rich history as a Spanish-American War artifact is no exception. With its enduring legacy as a sentinel of American history, the talented board of visionaries who have partnered with Beaufort County to breathe new life into this treasured landmark is equally intriguing.

At the heart of this effort is the vision of the late Pete Richards. This extraordinary leader helped rally a team of accomplished individuals with one shared mission: to reopen Fort Fremont as a welcoming, well-preserved destination for all. Each board member brings unique expertise, contributing to the transformation of Fort Fremont into a must-see site for locals and visitors alike.

Yet, before we delve into the specific contributions of this team, let’s explore the fort’s origins, which begin with Fort Fremont’s significant role in guarding the waters of Port Royal Sound and its enduring legacy as a sentinel of American history.

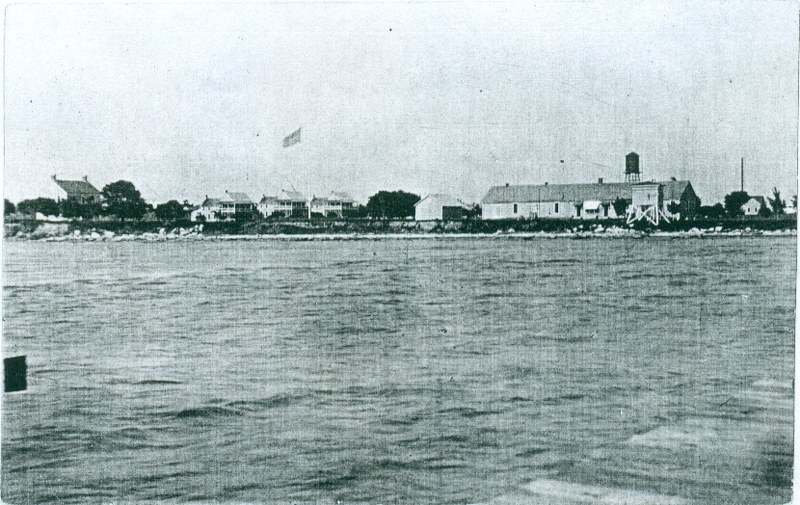

“Fort Fremont, built on 170 acres by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1898-1899, once housed a hospital and barracks, and still contains two batteries—Battery Jesup and Battery Finance.” Brigadier General (retired) George Barnette (Barney) Forsythe, PhD, a 35-year U.S. Army veteran and West Point graduate, explains.

Barney, now the Friends of Fort Fremont Board president, had moved to Beaufort, and his old friend Wendy Wilson asked him to become involved with Fort Fremont. Barney added, “Wendy’s brother-in-law was my college roommate.”

Barney is a passionate advocate for preserving history and is dedicated to sharing the significance of Fort Fremont with the Beaufort community, which he proudly refers to as his “home base.”

His wife, Jane, a retired early childhood educator, and Barney, a West Point professor and vice dean for education, raised their two children, Jennifer and Bryant, at West Point. Now living on Lady’s Island, Barney notes with a smile, “Six other West Point classmates happen to live here in Beaufort, too.”

Barney’s historical knowledge of Fort Fremont is apparent as he describes three key components for protecting the Port Royal area. First, three 10-inch disappearing carriage guns were intended to safeguard the Port Royal Naval Station on Parris Island. Second, controlled mines were implemented to mitigate threats to the Naval Station. These mines were not impact-detonated, allowing commercial traffic to navigate the Beaufort River without risking contact with the minefields. The third component was Battery Fornance, which featured two Armstrong quick-fire guns designed to engage any enemy ship that might attempt to breach the minefield by cutting the cables. “It served as an extreme deterrent which exceeded 35 feet in depth,” Forsythe shares.

The mines were deployed only during a few months of the Spanish-American War and then blown in place. In peacetime, they were stored at the federal arsenal in Augusta and would be brought down by rail when needed. They were then deployed in the Beaufort River by the Fort Fremont garrison. The mines served to prevent the passage of enemy vessels past the fort. They were detonated manually by soldiers in the casement on order.

Fort Fremont had electricity and a sewer system before Beaufort, but its role decreased as the war ended and the threat to the Naval Station subsided. The last unit was transferred in 1911, and a caretaker contingent from Fort Screven in Savannah kept watch until 1914, when the fort was deactivated. The land was put on sale in 1921, and the guns stayed until World War I, and there was not a lot of participation from the private sector. There was talk of other identities, such as Mr. and Mrs. G. B. Dowling turning it into a hunting and fishing lodge, but that did not come to fruition.

Fort Fremont was placed on the National Registry, and in 2004, Beaufort County and the Critical Land Program and Trust purchased the 15-acre site to transform it into a public park. In 2010, additional land was purchased, including 900 feet of beachfront property overlooking Port Royal Sound.

In 2006, Pete Richards and a group attended the Master Naturalist course offered on Spring Island, a private Lowcountry waterfront community and nature preserve. The Master Naturalist program is the flagship of the Spring Island Trust’s (SIT) educational initiatives, first established by Beaufort County Clemson Extension Agent Jack Keener. After Keener’s retirement, Clemson asked Spring Island to continue the program.

The program’s vision is to provide specific training for understanding natural landscapes, including underlying geology and the impact of human activities on the environment. It emphasizes the importance of conserving natural habitats. The education aims to prepare participants to become Master Naturalists involved in various volunteer projects. This class was held in 2006 and attended by many of his friends and people who had previously worked on projects Richards had initiated.

Richards lived with his wife and two daughters in Port Royal, and was known for starting and bringing community projects to success. A leading salesman with an incredible concentration in public relations in Atlanta, GA, Richards had a revelation: His respect for Fort Fremont was unyielding, and he immediately thought he could help. Pete was in the Navy during the Vietnam War and served in the brown-water navy on the Mekong River. His exposure to Agent Orange triggered the cancer that would prove fatal.

Richards decided to create a 501(c)(3) and call it the Friends of Fort Fremont Board. Richards, known for his energetic interest in exciting projects, also had the gift of finding the right people to join him in his pursuit. As Betsy Richards, his wife, adds, “Pete was charged with working on a 40-hour-a-year community project required from the Master Naturalist program. Calling on some of his fellow class members, he asked for help on the unkempt state of the fort and started to put together a group with different yet strong skills to help, including engaging the County.” She continues, “Pete has always been rooting for the underdog, and this project was a gem.”

Many surrounding Richards and on the Fort Fremont team were the following: Wendy Wilson has lived in Beaufort for 24 years. She moved to the town after serving as the Director of Marketing for a company in Alexandria with a contract for the Department of Homeland Security. Marion and Ray Rollings, retired Corps of Engineers and Air Force civil engineers with extensive experience, met while working on their dissertations at the Corps Geotechnical Engineering Lab in Vicksburg, Massachusetts. They frequently collaborated and lived in Beaufort with their extended family.

Although not on the Board but always there for support, Betsy Richards, Richard’s wife, was a retired childcare consultant who became a leading innovator at Brown Richards and Associates, where she focused on creating daycare centers for career women. Then Anne Kennedy, a longtime resident of Beaufort, was rounding out the group. She has been married for 57 years and has two sons and four grandchildren. Notably, her son married Patty Richards, Pete’s daughter. Anne first became acquainted with Fort Fremont as a young first-grade teacher at the old Beaufort Elementary School, where she was invited to dinner by a student’s family who lived in a house built on top of the Fort’s Battery Fornance. “I love Fort Fremont,” she stated clearly.

Past President Cecile Dorr and her late husband, Carl Dorr, were also involved. They lived in the eight-bedroom 1906 original Fort Fremont Hospital. Cecil, a librarian, and her husband, an engineer, raised their two daughters there. Cecil fondly remembers working with the group as a past president. She warmly remembers Pete as the “Idea Guy” and Wendy Wilson as a “The Wind Beneath Our Wings” board member who was always there to help everyone.

The members began meeting, and their dedication became unwavering after some time. Wendy Wilson recalls, “After Pete discussed the idea with us, the rest was history. I initially thought it was a six-month project. That was seventeen years ago.”

With no funding, there were obstacles. Ray Rollings stated, “The biggest challenge was convincing the County and the public that there was any history at the site.” That all began to change quickly when Ray and Marian Rollings put together a three-month exhibit on Fort Fremont at the Verdier House in 2012, which started to change the attitude locally. They later wrote a study of the durability and earthwork issues at the site; this included a petrographic examination of the concrete samples from Battery Jesup by Clemson University and their importance. This concentration of the conditions of the site was just the beginning. But Richards and his crew were steadfast, knowing that this hard work would benefit the fort and Beaufort County.

The importance of these many projects and the individuals involved with Fort Fremont was relentless. Part two of this article series will discuss the board members’ vast contributions.

Tops on the list are the critical structure of the Fort, which will continue to be vital as we delve into the contributions and the focus of Ray and Marian Rollings’ roles; the Rollings have extensive academic and practical engineering experience with these materials. “Fort Fremont poses a particular challenge in that it is composed primarily of Rosendale natural cement (the cement used in the Erie Canal and quite different from modern Portland cement), and used engineering and construction techniques different from today’s,” Ray explains.

The Rollings are an unusual couple in that they both have PhDs in civil engineering and have done extensive engineering work with the Corps of Engineers, Air Force, and others. Ray says, “Fort Fremont provides a frozen snapshot of various engineering and military issues of 1898-1911. Marion states, “Fort Fremont marks the end of 350 years of coastal fortification on Port Royal Sound and the opening of a new era that would see aircraft replace fortifications and large guns for coast defense. This property was farmland before. Nothing has disturbed Fort Fremont’s batteries since then.”

Much work is needed, including Wendy Wilson’s continued support of planning the special harvest events and marketing for fundraising—and the story of the building and deservedly named Pete Richards History Center.

Barney has begun with his West Point classmate, Pete Scullery, vice president of the Board, who is actively involved with a project with the cadets of West Point. To enhance the visitor experience, the Friends of Fort Fremont are partnering with the Center for Digital History at the United States Military Academy at West Point to create a digital simulation of the construction and operation of Fort Fremont,” Barney explains. The cadets will arrive in the summer 2025 to begin filming and gathering information. After a long career in education, Barney and the Board know this work is essential.

Stewarded by Richards, the Board’s dedication and commitment to Fort Fremont is evident. Betsy Richards says of her husband, “Pete used to say it’s a win-win situation for both the Board and Beaufort County.” As Pete Richards often said and valued, “Fort Fremont is the third gem of Beaufort County aligning with the Penn Center and Hunting Island.”

Their mission confirms preserving Fort Fremont as an educational, historical, and cultural resource of the Spanish-American War era on the shores of historic Port Royal Sound in Beaufort, South Carolina.

In the meantime, drive 7.5 miles from Sea Island Parkway to Martin Luther King Boulevard, which becomes Lands End Road, to visit the fort; check out their website, www.fortfremont.org; watch podcasts; and start your journey.